GitHub Lingo

- GitHub 101

- GitHub Lingo

- GitHub Issues

- GitHub Pull Requests

This blog series started as a lightning talk at the 2017 PowerShell/DevOps Summit titled “Being an Upstanding Gitizen.”

Table of Contents:

GitHub Lingo

Git and GitHub, for all their power, are not intuitive to get started with. We’re all git-diots, just at different points in the journey.

We can accelerate that learning curve (and save you some embarassment!), though, by walking through the basics. Here’s a primer on terms you’ll hear as you start to get involved.

(Once you know what you’re looking for, there’s also a wealth of information at GitHub Help.)

Git & GitHub

Git is a type of distributed version control system (DVCS). I’ll spare you the details; if you care about the question “Why Git?”, then start here: Git Basics.

Git was developed as a command line interface (CLI), but there are plenty of GUI options if you prefer.

GitHub is a free hosting platform for open source Git repositories. It’s intended to help you easily find/consume/contribute to/create/maintain open source projects.

GitHub allows you to search keywords for projects in your preferred language, check who contributes to that repository and when the last update was, see what else the owner has worked on, and so on.

Projects/Repositories

The terms “project” and “repository” are typically used interchangably in GitHub land. Your repository (“repo”) is the collection of files and folders–consisting of code/docs/images/etc.–that make up your project.

One caveat: GitHub has a “Projects” tab that is intended to be used like a Kanban board. I find that this isn’t used very often in practice, but FYI to head off any confusion.

Star/Watch/Follow

“Starring” a project is giving it a like/favorite. Your profile keeps a list of repos you’ve starred, for quick future reference.

“Watching” a project and “following” a user mean that you’ll receive updates on the project’s/user’s activity on your GitHub dashboard after you log in to the site.

READMEs

At the root level of each project’s code, there should be a README.md file. Just below where you see the code listed on the repo’s main page, you’ll see that README, just like if you were looking at a Word doc. Generally, it’s used to explain why the project is useful, what is possible, how you can get started…and a variety of other things.

.md is Markdown. It’s a convenient syntax to easily format your plain text documents. You can learn it by tinkering on Dillinger.io. Note that GitHub uses GitHub Flavored Markdown, which basically means they’ve layered some extra features on top.

Issues

Think of the Issues tab like the helpdesk. If there’s no ticket, it doesn’t exist. Bugs are tickets. Feature requests are tickets. Questions can be tickets. And like a helpdesk ticket, issues should be triaged before they’re closed, so the more info you can provide up front, the better.

“My email doesn’t work…”

Don’t be the stereotypical Janice from Accounting. Some examples of helpful info you could provide:

- Current behavior

- If a bug, steps to reproduce

- Expected behavior

- Possible solution

- Other context

- Your environment

- OS, PowerShell version, module versions, etc.

Oh, and welcome to QA, haha

Commits

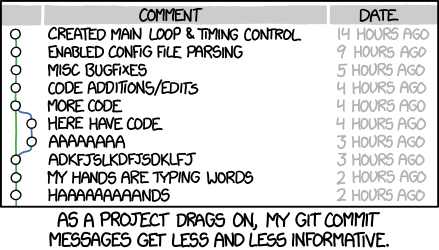

Commit = snapshot. Each commit tracks what files were added/removed/updated since the prior commit. Your project is just a series of commits that track your progress from the beginning until now. #existentialism

Commonly, commits are used to view differentials (diffs), where two versions of the file are lined up side-by-side while highlights show where changes occurred.

Each commit has a unique hash code ID. If you see a long hexadecimal string (or the short seven character version, like f2ae3b6), it’s probably referring to a specific commit.

Sync/Push/Pull

Because Git is distributed version control, it’s common for your local copy to be out of sync with the remote repo.

Once you commit, before those commits are seen by others, you would need to git push the changes to the remote. On the other hand, if you want to check and see if anyone else’s updates have caused your local project to be outdated, you could git pull to check.

(Excuse the Git CLI commands, but you may see that terminology even if you do use the GUI.)

In GitHub’s GUI client, you’re given a “Sync” button that will both push and pull.

Coffee break

All of this has been teaching you words that allow you to laugh at more things on the Internet. Because really, why else are we online?

Forks

By default, you have read-only permissions to other people’s projects. (You can create new issues and comment on existing, but little else.) To propose changes to someone else’s project (docs, code…anything), you’ll need to fork the project first.

Simply: If you want to change a repo, you have to fork it.

Forking creates a point-in-time copy of the repository under your username, which you can edit/delete all you please without affecting anything. This is where you can modify the code and see if it works the way you intend it to.

If I fork PowerShell-Docs, the “upstream” PowerShell/PowerShell-Docs repository continues doing its thing, and all that changed is the little Fork counter in the top right. Ta-da: I’m the proud new owner of a “downstream” brianbunke/PowerShell-Docs repository; anyone can browse it, but only I can edit.

Now I can make changes to my heart’s content, and my fork will track how many commits ahead and behind it is in relation to the original repo. (Because forking is a point-in-time copy, any future commits the main repo makes do not automatically apply to your fork.)

You can only have one fork of each repository. You cannot fork your own repository.

But any commits you make in your fork won’t automatically make it back to the main project. Read on…

Branches

Ok. Honestly? A branch is like a parallel universe. What if the sun always screamed? What if Earth was ruled by apes?

Each repository begins with a single master branch. This is your main area of the project. It’s possible to do everything in master, but that’s basically like testing in production.

What you should do–if you’re brave enough to bring the hypothetical into reality–is create a new branch and name it apes, or feature-strength, or permanent-sweater, or whatever.

In that new branch, you can edit your code to change all humans to apes. By isolating this work to a branch, you are not affecting work that you or anyone else is doing to the master branch.

A repo can have many different branches, because there are many different alternate dimensions. (Duh.) When you fork a repo, it copies over all branches by default, since you might want to use any or all of them. Once you have forked, both projects could continue to branch and commit, independent of each other, forever.

You remove branches in two ways: either your work was successful and you merge it back into its parent branch, or you delete it and discard that effort.

Sometimes, owners use “protected” branches, which typically means that you can’t immediately commit to master even if you have write permissions to the repo. In that scenario, how would you make changes to master? Glad you asked…

Pull Requests

A pull request (PR) is a request to add/delete/modify part of the project. It’s named that way because you are requesting that the owner/maintainer pull in your change(s) to the main project.

If you want to submit changes for someone else’s project, it happens via a pull request.

Pull requests are where the “code review” process comes into play. Your pull request lists all the commits that were made on your branch, all the files that would change if it is merged (accepted), and the diffs between the files that would be updated. As with a single commit, each PR could affect entire files and folders, or be targeted at a single line or word.

The pull request is then open for comments from interested parties. It can remain open while discussion occurs, which sometimes is a request for the submitter to make an additional commit on the source branch to fix something.

Pull requests are always a comparison between two branches: a source and a target. Everything that is different in the source branch will be changed in the target if the PR is approved. (This is why smaller branches and smaller PRs are generally recommended.)

fork:bugfix-branchintomain:masterfork:feature-branchintomain:develop-branchmain:patch1intomain:master

Note that the first two examples show a forked project proposing a change to the upstream (parent) repository. A common workflow to propose a fix would be: fork a project, create a new branch, make a targeted change, and submit the change as a PR.

The third example is two branches in the same repository. Normally, this could be done as a merged branch in a normal commit. However, if master is set as a protected branch, the PR process would handle the code review before patch1 is allowed to affect the main branch.

Since PRs work with branches, an accepted PR is “merged” into its target branch. Eventually, all PRs are closed, whether they were merged in or not.

We’ll walk through a basic pull request later this week.

Key Takeaways

Hopefully, with this terminology in your pocket, you can at least feel more comfortable in conversations. If you feel like you’re able to better search for any Git/GitHub problems you run into, and more easily follow the resolutions, that’s the ultimate goal.

Learning is foundational. With the vocabulary established, now we can start building on top of that.

Up Next

Making your first GitHub contribution! Tomorrow will be all about issues: why they’re important, and how to do them the right way.

Acknowledgments

- @markwragg for suggestions. Thanks!

- In Case of Fire and xkcd for the laffs

- lipkau for reminding me of GitHub’s projects tab